“Although I believe the fault primarily lies with the government and TEPCO, in a sense each and every one of us has a degree of responsibility. I hope we will all use this opportunity to take a fresh look at ourselves. This could be the impetus for society to change.”

scroll

- ProfileRuiko Muto

- Ruiko Muto lives in the town of Miharu, Fukushima prefecture. She and a group of friends formed the "Fukushima No-Nukes Network" in 1988, after the Chernobyl disaster prompted her to become involved in the anti-nuclear movement. In 2012, Muto became leader of the "Complainants for Criminal Prosecution of the Fukushima Nuclear Disaster," a class action lawsuit seeking to hold the former management of TEPCO criminally responsible for the Fukushima Daiichi disaster.

A longtime opponent of nuclear power, Fukushima native Ruiko Muto has spent over 30 years involved in the anti-nuclear movement. When the Great East Japan Earthquake struck in March 2011, Unit 1 of Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant was already an aging reactor that had been in operation for 40 years, and had seen its share of small accidents and mishaps. Muto was left stunned by the disaster that unfolded on her doorstep, and initially she found herself struggling to decide the right course of action.

“Nothing to see here…” - The government propaganda machine swings into action

Following the multiple explosions at Fukushima Daiichi, Muto made up her mind to head west. She knew that Unit 3 was a MOX reactor*, which only increased her concerns. Muto’s home is 45 km to the west of the plant, and her home was not subject to an evacuation order. On the contrary, the town was actually taking in evacuees from areas closer to the plant. In the first days of the disaster, it felt as if the evacuation zone was expanding by the hour as the situation developed. On the night of March 12, everyone within a radius of 20 km of the plant was ordered to evacuate, while three days later on March 15, all residents living within 30 km were instructed to stay indoors.

Looking back at these early days, “The official response astonished me”, Muto recalls.

“Did they really think an evacuation area of only 20 km would be sufficient? At the minimum, I expected they would take children further away, and provide assistance for disabled people who had difficulty evacuating - but there was nothing like that. As soon as disaster struck, it became clear that the evacuation plans that the plant operators had set out on paper weren’t fit for purpose.”

The Fukushima Daiichi disaster was rated category 7, on the same level as Chernobyl. Many of the people who had spent years in the fight against nuclear power felt that a disaster on this scale would become a turning point, forcing Japan to change course on its nuclear policy. The shock of the Great East Japan Earthquake led to something of a public reevaluation of the modern Japanese lifestyle, characterised by an endless search for greater convenience and casual luxury. The inherent problems of nuclear power were thrust into the public eye, and suddenly energy policy became a talking point. People who had never paid any attention to nuclear power before were caught up in a wave of anti-nuclear sentiment that swept the country.

With the benefit of hindsight, it’s clear that this was a transient awakening. But even as this new movement gathered pace, back in Fukushima prefecture the government was springing into action with the opposite message - a campaign to convince the public that ‘Fukushima is safe.’ Safety advisors were deployed around the prefecture to spread the message that an annual radiation dose of 100 milliSievert (mSv) is perfectly safe, even in the case of pregnant women and infants, and that there was no problem letting children play outside. This message was completely at odds with the ‘precautionary principle.’ Watching as this efficient messaging machine was rolled out by the authorities, Muto realised that any hope that the disaster would spell the end for nuclear power in Japan was badly misplaced.

“The disaster was being downplayed, the facts were being obscured, and the state was not supporting the victims in the way they needed. Before the accident, the radiation exposure limit considered tolerable for public health was just 1 mSv/yr, but suddenly the messages coming out of the government were suggesting that exposure of up to 20 mSv/yr is absolutely fine. I had been holding onto a small hope that a change in direction was on its way, but that hope evaporated in front of my eyes.”

Over the past few years, Fukushima prefecture has been experiencing a slew of new projects that not only seem to water down protective safeguards, but would appear to be forging ahead virtually unchallenged. Forests contaminated by radioactive fallout are being burnt in the name of ‘biomass power’, recycled soil is being used for growing vegetables, and it is being proposed that contaminated water may be flushed into the ocean after processing which it is claimed will have made it safe. Dissenting voices have been shut down.

“A lot of companies with connections to the power and nuclear energy industries are getting involved in the cleanup work, for example decontamination and incineration”, says Muto. “Of course, everyone wants to see the region prosper again. But when it comes to these types of schemes, I see them being pushed forward under the guise of ‘recovery projects’. In reality, a lot of the time this is simply a concept that is being cleverly manipulated in order to win over public sentiment.”

The balance between ‘recovery’ and ‘legacy’

2016 saw the opening of Commutan Fukushima, an ‘Environmental Creation Centre’ in Muto’s hometown of Miharu. Elementary school students aged between 10 and 12 visit on school field trips from around Fukushima prefecture in order to learn about radiation and the aftermath of the Fukushima Daiichi disaster.

“A lot of the children come away saying things like ‘I used to think radioactivity was scary, but now I feel reassured’. I find that very conflicting”, says Muto.

Critics have pointed out that the displays focus more on the recovery efforts than on the hard lessons that need to be learnt from the disaster. A closer look at the language used in the center’s explanatory panels shows a disproportionate number of words with positive connotations; when the most frequently appearing terms are ranked, anzen (‘safety’) and riyou (‘beneficial utilisation’) come near the top of the list. By contrast, the Chernobyl memorial museum makes heavier use of words such as ‘accident’, ‘contamination’, and ‘deaths’, apparently without feeling the need to accentuate the positive. The primary role of educational facilities such as this should be to provide a factual record of the events and their consequences, with a focus on preventing the same mistakes from being repeated in the future.

In 2020, the ‘Nuclear Disaster Memorial Museum’, funded by the Japanese Government to the tune of 5.3 billion yen (about 51 million USD) , opened to the public in the town of Futaba, only 4 km away from the Fukushima Daiichi reactors. Although the facility claims to use videos and text to explain how the disaster unfolded, personal testimonies of the disaster and actual artefacts are few and far between. There is no mention of regret or lessons learnt. Some residents have complained that it is not clear what message the museum is trying to deliver. On their way to visit the museum, groups of middle and high school students are driven past a vast expanse of contaminated waste lying indefinitely in ‘intermediate storage’.

“I think there is an element of dishonesty in how children are being educated about the disaster. Key facts are being left out of the discussion. Recently, delegates from the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry (METI) have been going around schools in Fukushima giving presentations on the appropriateness of releasing contaminated water into the ocean. I can’t reconcile the way these projects are being used in an attempt to reprogram how the younger generation sees the disaster, especially when you consider the huge amount of money and the systematic approach being taken.”

Taking recovery hints from the town that produced the Nagasaki bomb

Fukushima prefecture is now promoting an economic recovery scheme dubbed ‘Fukushima Innovation Coast Framework’ focused on the Hamadori area – the part of the prefecture stretching along the Pacific coast and most directly affected by the tsunami. A vast recovery budget is being channelled into buildings and civil engineering, the Memorial Museum being a prime example of this. When this project was first introduced, the government touted the US town of Hanford, Washington as a model city. This town is where the plutonium that went into ‘Fat Man’, the atomic bomb that was dropped on Nagasaki, was refined. Although Hanford’s nuclear complex is long gone, the region is heavily contaminated to the extent that it was once known as ‘the most polluted place in America’. However, research organisations and companies with a focus on decontamination and environmental restoration have moved in to fill the gap, and Hanford is booming. To this day, atomic energy enjoys popular support in Hanford. Now, the Japanese government is hoping Fukushima will follow this model.

“When a town that hosted a nuclear plant falls victim to an accident, it should be a golden opportunity to divest itself from that industry. But perversely, we’re opening the door to allow new nuclear projects to come in. I can see us becoming dependent on the atomic industry all over again for the sake of development. I worry that if we’re not careful, we’ll be carried away on this government-driven model of ‘recovery’ that actually leaves the victims behind.”

Reaching out while looking forward

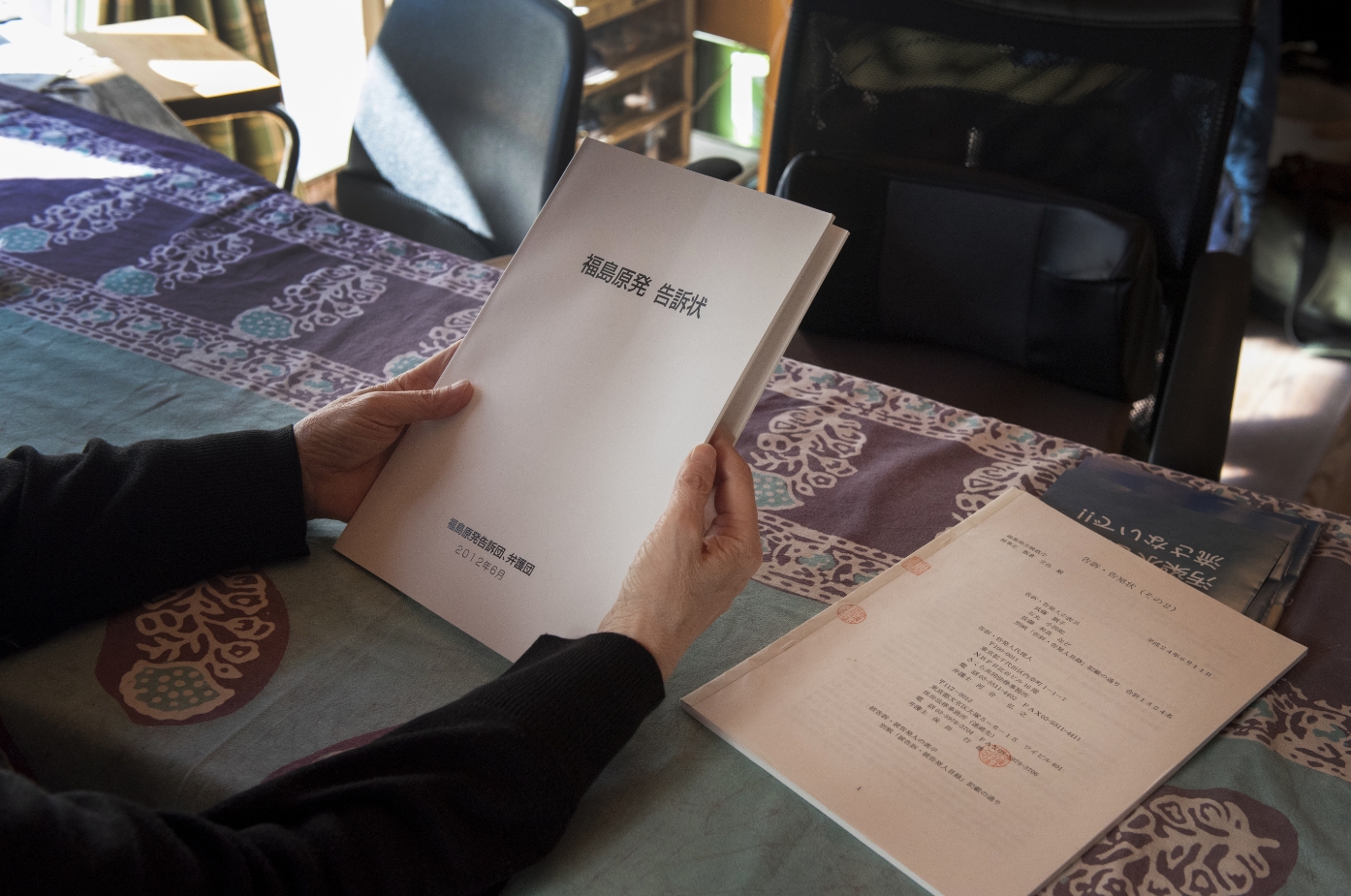

Muto was one of the founding members of Complainants for Criminal Prosecution of the Fukushima Nuclear Disaster in 2012, launching criminal proceedings against the former management of Tokyo Electric Power Company (TEPCO)**. The journey to trial took five years, and the case still drags on. A number of plaintiffs have already passed away without ever seeing a resolution. Across Japan as a whole, over 30 class action lawsuits relating to the Fukushima Daiichi disaster have been brought against TEPCO and the Japanese government. The majority of these cases focus on establishing responsibility, an issue that has never been laid to rest.

“When we decided to pursue legal action, I struggled with the idea of accusing someone of a crime. But the real aim of this trial is not to condemn anybody, but rather to allow the courts to establish not only where the responsibility lies but also the nature of that responsibility. From there we can start working together to avoid repeating the same mistakes in the future. Of course, fighting it out in court is a polarizing process by definition, but I believe it’s something that is necessary if we are to find a way forward from here.”

This class action has now gathered 14,716 complainants. One prospective complainant, from outside Fukushima, was initially unsure about being allowed to participate feeling that as an outsider they bore part of the responsibility for Fukushima’s collective suffering, as they had been willing to let the communities around the nuclear plant take the risk while enjoying, at a safe distance, the benefits of the electricity produced.

Muto’s personal take on the question is this:

“Although I believe the fault primarily lies with the government and TEPCO, in a sense each and every one of us has a degree of responsibility. Excluding children, everyone in society is partly to blame – even myself. I hope we will all use this opportunity to take a fresh look at ourselves. This could be the impetus for society to change. If we don’t treat this as a problem unique to Fukushima, but something that involves all of us, then maybe we can all move forward together.”

Six months after the Fukushima Daiichi accident, Muto gave a speech at an anti-nuclear rally that drew 60,000 attendees. Here, she made the point that every time we casually plug in an electrical appliance, we should think about what happens “on the other side of the socket”. It takes a certain degree of imagination to consider the inequality and sacrifice made for the sake of our convenience. Her expression “the other side of the socket” refers to the whole, often opaque, nuclear energy industry. Muto wants us to realise that the people living near “the other side of the socket” are no different from anybody else – they just want to live quiet and decent lives. Drawing a line in the sand between “us” and “them” only serves to further widen the divides that spread through Fukushima after the accident.

Muto ends on an optimistic note.

“Young people are starting to get involved too. The various legal cases have seen a number of small victories. Although there will also be plenty of setbacks, I believe we will gradually move forward as a society. Change will always take time, but all our small efforts add up. All we can do is persist, and continue to stand up for what we believe – all of us.”

- *MOX reactor: a type of nuclear reactor that runs on MOX fuel, produced by extracting plutonium from spent nuclear fuel and mixing it with uranium. MOX fuel generates more radioactivity and heat than uranium-based fuel, and is more difficult to control. There is a risk of releasing large volumes of plutonium into the environment in the event of an accident.

- **Fukushima Daiichi criminal case: A case to establish TEPCO’s responsibility for the Fukushima Daiichi accident on the grounds that the accident would have been preventable had TEPCO not neglected to take action despite having been warned about the possibility of a tsunami of the scale that was seen on March 11th. Although the state prosecutor repeatedly declined to lay charges, a citizen-led prosecution examination committee forced a mandatory indictment. The initial trial returned a verdict of not guilty. The prosecution-appointed lawyer appealed, stating “This decision was made in deference to a government tied up in the nuclear industry. If this verdict is finalized, it will be a clear violation of justice.”