“As long as we hold onto nuclear power, the things that happened to me could happen to you at any moment. On March 11th, I crossed the threshold and was forced to leave my old life behind. You, on the other hand, are still living on March 10th, and you have a choice. Your March 11th could go one of two ways.”

scroll

- ProfileMizue Kanno

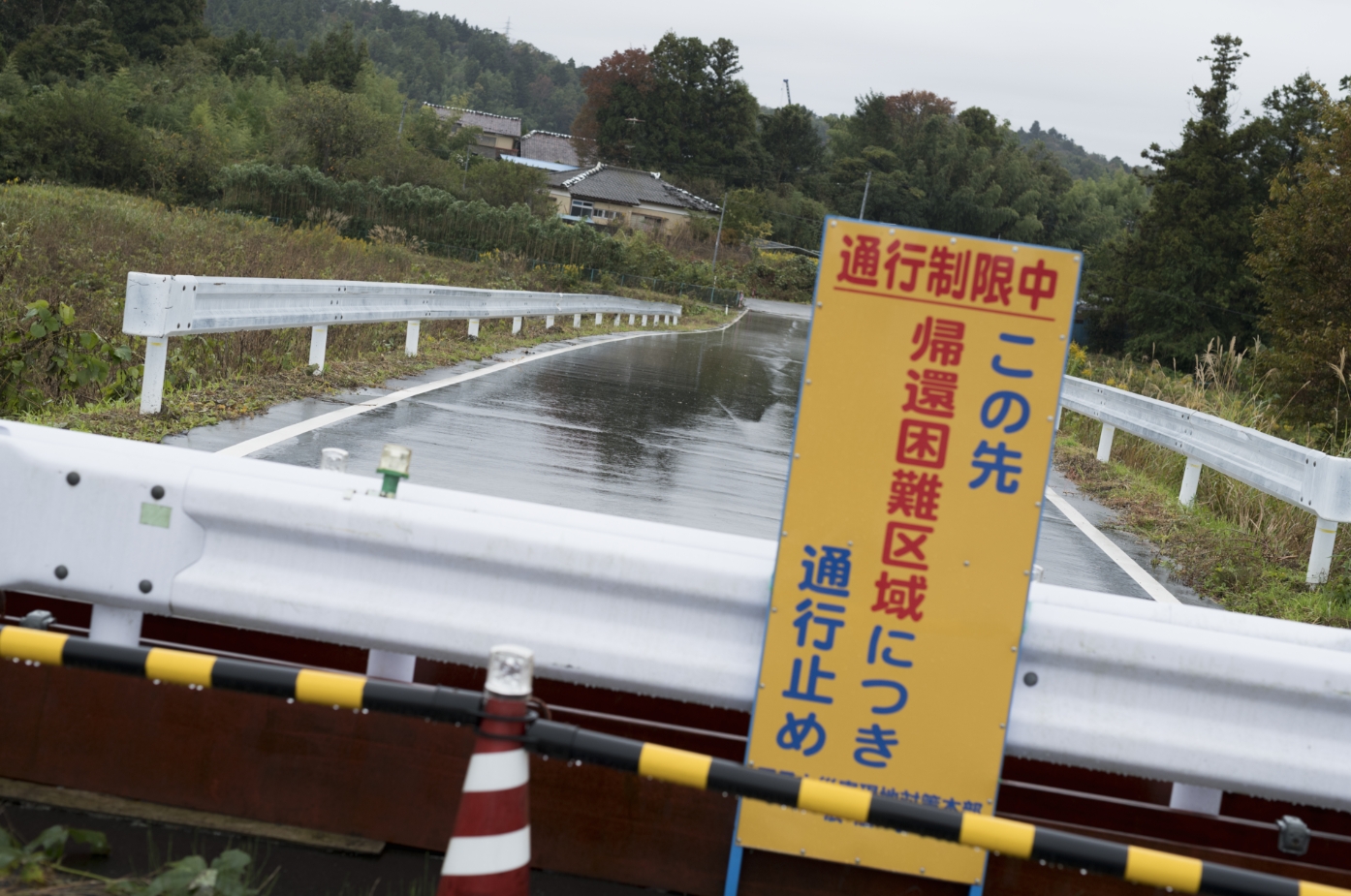

- Mizue Kanno lived in the small community of Tsushima within the town of Namie, Fukushima prefecture, until radioactive contamination from the accident at the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant forced her to evacuate. After spending several years in temporary housing within Fukushima prefecture, she relocated to Hyogo prefecture in 2015, where she now lives together with her family. Her former home in Namie is within what is classed as a ‘difficult-to-return’ area, with no prospect of becoming inhabitable in the foreseeable future.

The unusually-shaped town of Namie has an eastern portion on the Pacific coast, narrowly linked to an inland portion stretching toward the north and west. The town hall is located on the eastern, coastal side of town, only 8 km away from the remains of the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant operated by Tokyo Electric Power Company (TEPCO). The town suffered heavy damage from both the earthquake and tsunami in the Great East Japan Earthquake of March 11th, 2011. Despite its proximity to Fukushima Daiichi, since the plant is technically outside the town’s boundaries, there were delays in relaying information to officials in Namie as the situation deteriorated. However, sensing that the town was in danger, on the day after the earthquake the local authority took the initiative in asking residents of the coastal side of the town to evacuate to Tsushima, a mountainous district in the northwestern sector. A resident of Tsushima, Mizue Kanno opened her doors to friends and relatives who had nowhere to stay. No one realised it at the time, but Tsushima itself had been subject to very high levels of radioactive fallout in the early stages of the accident. This fact did not become public knowledge until much later.

Plunged into chaos

Kanno’s former home is around 27 km from the Fukushima Daiichi plant. Initially, it was assumed that Tsushima was too far away to be affected, and the town hall had identified it as a place of safety. However, on the evening of March 12th, one day into the accident, Kanno saw a car full of what appeared to be scientific investigators, wearing full protective clothing and gas masks. Without even leaving their vehicle they warned her to leave the area immediately. Later that night, the Japanese government extended the evacuation zone to everywhere within a radius of 20 km around the stricken plant. Sensing that they were not safe, Kanno urged the friends and relatives who had gathered at her house to get themselves even further away. Kanno insisted that those in the group who had breastfeeding infants should leave immediately. The remaining members spent the night at her house, but the following morning they all went their separate ways. “Get as far as you can with the fuel in your tank!”, Kanno urged them as they departed.

Kanno herself did not evacuate until three days later. In the absence of an official evacuation order for Tsushima, the majority of residents were still there. When she spoke to neighbours, many simply refused to believe that they could be in any danger, with one exclaiming full trust in the nuclear plant’s safety. Since Kanno’s family were helping out at a local evacuation center, they stayed at home until March 15th, when the local authority reached the decision that the entire town had to be evacuated.

“I’d assumed that a company as big as TEPCO would have everything planned out in the event of an emergency. After all, how many times had they reassured the local community how resilient they were to disaster?”

Kanno had moved into her husband’s family home in Tsushima four years earlier, back in 2007. A traditional Japanese house, they spent over three years carrying out renovations, and in fact finished their restoration project only eight months before the Great East Japan Earthquake struck. Tsushima proved to be a welcoming community pleased to accept a new ‘outsider’, but was at its heart still a tight knit hamlet. As many households shared the same surname, everyone addressed each other on first name terms, regardless of age or status. Kanno’s house was surrounded by a large garden where her son had often played when he was younger. She had been looking forward to the day when she could install a swing for her grandchildren to play on, just as her own son had.

In the event, Kanno was forced to leave it all behind - her house, her belongings, her garden, her new community, the densely forested mountainsides, and all the memories that went with them.

Exposure level off the charts

After the evacuation order was issued on March 15th, Kanno finally left Tsushima. She was screened for radiation on arrival in the city of Koriyama, 50km to the west.

“When they held the Geiger counter against my jacket and hair, the needle shot right up to a hundred thousand cpm*. I didn’t really realise what that meant until much later. But no one kept an official record of the reading, neither the Fukushima authorities nor the central government. It makes me think they realised how much trouble there would be if word got out that members of the public had been exposed to that sort of radiation. The incident shook me up, and that feeling of unease will never leave me as long as I live.”

In 2016, Kanno was diagnosed with thyroid cancer. However, due to the lack of any official record from her initial screening, it has been impossible for her to prove a link to the radioactive fallout she was exposed to in Tsushima.

“I know a shop near the Fukushima coast that sells clip-on collars for T-shirts and wide choker-style necklaces. The shop owner told me that there’s a lot of demand for accessories that can hide the marks left behind by thyroid surgery. I’ve seen young women with surgical scars on their necks that are much bigger than mine. I’m getting on in years, so it doesn’t matter so much to me, but I wish I was able to trade my scars for theirs.”

It was not only the residents of Namie that lacked information about Fukushima Daiichi – even the local authority was left out of the loop. The Japanese government had carried out radiation modeling using a crisis management simulation system called SPEEDI, and had identified the possibility that a radioactive plume, in other words a cloud of highly radioactive particles, could have drifted in the direction of Tsushima. Although the prefectural government of Fukushima was aware of these modelling results, the information was never shared with Namie town hall, a fact that only came to light two months after the accident. Namie’s former mayor, the late Tamotsu Baba, was livid with the Fukushima government official who came to apologise later:

“If we’d have known about these models, we would never have told our citizens to seek shelter in Tsushima. There were children playing outside in front of the evacuation center, for heaven’s sake! As far as I’m concerned, you’ve as good as killed people by not telling us.”

Animal suffering caused by human arrogance

In the rush to evacuate, many people had no choice but to leave their pets behind. Evacuation centres had a ‘no pets’ policy, and the buses used in the evacuation even refused boarding to people carrying pets. Some owners released their dogs from their leashes before leaving, in the hope that somehow they would manage to survive by themselves. Still others, not realising how extensive the contamination was, left their pets at home assuming they would soon be back to collect them. Those who took animals with them were not allowed to bring them inside the evacuation centers. Kanno remembers seeing dogs locked in cars, mentally anxious and bleeding from self-inflicted bite wounds.

Amid the unprecedented chaos of evacuating an entire town, many people were heartbreakingly left with little choice but to leave cats and dogs behind. Of course, that did not stop internet trolls from calling them out: “Look at them running away but not bothering to take their pets with them!”

“As we started to realise evacuation was going to drag on indefinitely, people tried to go back to pick up their pets or check on livestock only to find that barricades had gone up and their homes were out of bounds. I know of one man who searched and searched for his missing dog, and when the dog finally turned up it had been rescued and taken to the neighbouring prefecture.”

Kanno was fortunate enough to be able to take her beloved dog Matsuko with her during the evacuation. When she moved into longer term temporary housing, there was a special block reserved for pet owners, meaning she was able to live together with Matsuko. However, the first winter after the disaster, Matsuko suddenly developed the blood condition thrombocytopenia, and died from internal haemorrhaging. Kanno remembers her dog coughing up blood that stained the surrounding snow red, and that her loyal pet in the cramped prefabricated apartment that they shared had never suffered from ill health before. Kanno has a theory that Matsuko’s coat picked up radioactive particles that had settled on the ground, which she then carried around with her to result in a much heavier dose of exposure.

“When I took Matsuko to see the vet, I asked whether her sickness could have anything to do with the radiation from Fukushima Daiichi. His response was that we don’t even understand the effects on people yet, let alone animals. I wanted to get an autopsy done on Matsuko, hoping it might be useful for other people in the future, but there was nowhere prepared to do it.”

The incident left Kanno with a new realization: “We’re like guinea pigs – but worse off.” She was used to hearing the residents of Fukushima described as ‘human guinea pigs’, but, she reflected bitterly, at least guinea pigs are tested and analysed in the laboratory. We can’t even get tested. If there is no testing, there is no data, making it easier for the powers that be to pretend nothing has happened.

As her home had been selected as a ‘model decontamination area’ in Namie, Kanno was permitted to return home for brief periods. She took the opportunity to take Matsuko’s body back to the house, and buried her under a cherry tree in the garden. Still holding onto the hope that one day it would be possible to examine her further and establish the cause of death, she chose not to cremate Matsuko, instead burying her body intact.

Matsuko may have been the first, but she was not the last. Over the following years, pet dogs of all breeds and ages fell victim to cancers and other illnesses. Kanno’s temporary housing block included forty units reserved for pet owners, but she relates how by the time she left four years later in 2015, hardly any of the dogs were still alive.

“After all the humans left, the dogs left behind in Tsushima became feral and started breeding. I would see packs of dozens of dogs roaming the area when I went back to check on the house. It was the first time I’ve felt threatened by dogs, to the point that I was afraid to go outside. I don’t think they were aggressive just because they were feral – I think it’s because they remembered how humans had betrayed them. The local cattle farmers also released the cows from their sheds before they left, and back in the summer of 2011 I would see herds of cows still wandering around. They were very tame, and would wander over to see what we were doing. But whenever I looked into their gentle cow eyes, I saw the cruelty of humans reflected back.”

Like snow in a gloomy depression

Kanno is also a survivor of the Great Hanshin earthquake of 1995. As a care worker, she patrolled the devastated streets of Kobe to check on the welfare of the elderly and disabled. Back then she saw the squalor of the cheap temporary accommodation from the perspective of an outsider. Little did she think that one day she would be living in similar circumstances herself.

“I’d wake up itching in the night to find red ants swarming across my futon. My neighbour’s smoking habit would turn the air in my own room purple. In summer, the sun beating down on the thin metal roof and metal frame sent the temperature up to 40 degrees, while in winter the lack of insulation turned the place into a fridge. The bath was just a simple tub, so I’d be sitting in the bath freezing from my bottom upwards!”

The occupants of the temporary housing unit organized themselves into a residents’ group and made repeated petitions to the local authority, as a result of which conditions improved slightly, but it was still far from a comfortable lifestyle. The many temporary accommodation sites that took in long-term evacuees around the region had different policies depending on the local authority, but the town of Kori where Kanno found herself living was relatively accommodating, allowing residents the use of municipal facilities as quasi-permanent residents.

The temporary housing was home to many elderly people in need of care, but although the local authority would provide help in the most severe cases, they were not able offer a full range of support. As a former care worker herself, Kanno set up opportunities for the elderly residents to get together, and the residents supported one another.

“Times were tough, but we cheered each other up, and we’d even organise girls’ nights for the old ladies. I do have some good memories from the temporary housing. But at the same time, I experienced how tough it can be to live in an unfamiliar area. The hardest thing was the treatment we got from some of the local community.”

The evacuees faced stigma from the association with Fukushima Daiichi, radiation, and evacuation itself. The lack of clear and accurate information from the government resulted in an endemic lack of understanding in the wider community. Misunderstandings over the compensation system in particular saw the evacuees come in for harsh criticism: “I’ve heard you’re doing nicely out of all the compensation money! I’m paying for that with my taxes, you know!” Misinformation and distrust ran rampant through society in the uncertain years following the disaster. Kanno feels that evacuees made convenient scapegoats for the wider fears of society.

“Although snow blows in every direction in a snowstorm, it doesn’t build up on the high ground. The wind blows it down to the lowest points in the landscape. Even after the thaw, the drifts in these gloomy depressions remain. As an evacuee, you’re like that stubborn snow that won’t go away.”

A plea to those living on “March 10th”

Several times a year, Kanno still visits her former home in Tsushima to check on the building and pay her respects at the family grave. The building has now decayed to the point where it is impossible to imagine living there again, the garden overrun with undergrowth and saplings. Despite all her affection for life against the rich natural backdrop of Tsushima, Kanno has now relocated to a traditional house in Hyogo prefecture, where her family have reunited. Unable to contemplate a cramped urban lifestyle, they bought a home in a remote rural community. Japan’s geography means that nowhere is truly far from a nuclear plant, but one of the deciding factors when settling on Hyogo was that the closest plant is 80 km away.

As a member of the generation that allowed Japan’s nuclear plants to be built, and as a victim and evacuee herself, Kanno believes she has a duty to pass on her experiences or risk becoming part of the problem. She shares her experiences in public when she can, and has become a campaigner against nuclear power, fighting plant restarts and identifying flaws in evacuation plans. When she visits the communities that host nuclear plants, she asks local council employees “Do you have what it takes to provide support even when you’re a victim yourself?”

“What I discovered from being an evacuee was there are limits to what you are able to do for yourself in an emergency. No matter how hard you try, to some extent you will always be dependent on the authorities. Local council workers have to bear the brunt of the frustration of their neighbours, even though they may well have suffered just as much themselves. People working for the prefectural or central government don’t have to deal with that. I’ve seen exhausted staff at the town hall in tears while being berated by angry residents, protesting that they are victims themselves. Surveys have found very high levels of mental illness among local council workers in the disaster area.”

When Kanno speaks publicly, there is a metaphor she likes to use:

“As long as we hold onto nuclear power, the things that happened to me could happen to you at any moment. On March 11th, I crossed the threshold and was forced to leave my old life behind. You, on the other hand, are still living on March 10th, and you have a choice. Your March 11th could go one of two ways. Which path will place the smallest burden on our children and future generations? As adults, I urge you to think carefully.”

- *cpm: A unit of the radiation detected in one minute by a radiation detector, used with Geiger counters and other devices for measuring radioactive material adhering to the surface of clothes or the body. Fukushima prefecture’s ‘Exposure emergency medical response manual’ at the time recommended thyroid screening and iodine tablets for anyone with a reading of 13,000 cpm or higher at the time of evacuation.