“The government claims that a bit of decontamination work can fix the problem, but because we have measurement data, we are able to show that the problem hasn’t gone away at all.”

scroll

- ProfileMai Suzuki

- Mai Suzuki has been involved with the international environmental organisation Greenpeace since 2003. Since 2012, she has acted as their radiological protection advisor. In this role, she has visited Fukushima every year since the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster as part of Greenpeace’s annual radiation survey team.

The radiation released into the environment in the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear accident fell onto the prefecture’s mountainsides, fields, and gardens, into the rivers and sea, onto roads and roofs, and onto the people themselves. The effects of this contamination will be long-lasting; for example, it will take 30 years for just half of the isotope cesium 137 in the environment to decay naturally. For the people of Fukushima, life was turned upside down on the day of the nuclear disaster, with communities and livelihoods being transformed overnight, even down to what was safe to eat and drink. The radioactive contamination that lingers in the environment has no colour, taste, or smell, with the only way to render it ‘visible’ being through careful scientific measurements.

Exposing the invisible

Mai Suzuki explains the importance of her role as Greenpeace’s radiation protection advisor in the annual radiation surveys the organisation undertakes in Fukushima prefecture, "Putting a numerical figure on the level of radiation out there is obviously central to judging whether or not a given location is safe, but it also helps demonstrate the responsibility of Tokyo Electric Power Company (TEPCO) and the government in concrete terms. For example, the government claims that a bit of decontamination work can fix the problem, but because we have measurement data, we are able to show that the problem hasn’t gone away at all."

The Japanese Ministry of Environment began decontamination efforts in some of the affected areas the year following the disaster. In practice, ‘decontamination’ means removing topsoil and vegetation on which radioactive material has settled, as well as cleaning building surfaces, in an attempt to lower the airborne radiation level. The soil collected in this decontamination work is transported to temporary storage sites around the region to be held in ‘intermediate storage facilities’. The government line is that decontamination effectively removes radioactive material, but in practice things are not so straightforward. Although the decontamination efforts have shown some degree of success in certain areas, in more rural communities meaningful decontamination is difficult to achieve. Even if topsoil is removed and replaced, wind and rain leach more contamination from the surrounding untreated terrain, resulting in recontamination. Greenpeace’s surveys have highlighted the complex natural processes that bring fresh contamination to decontaminated land.

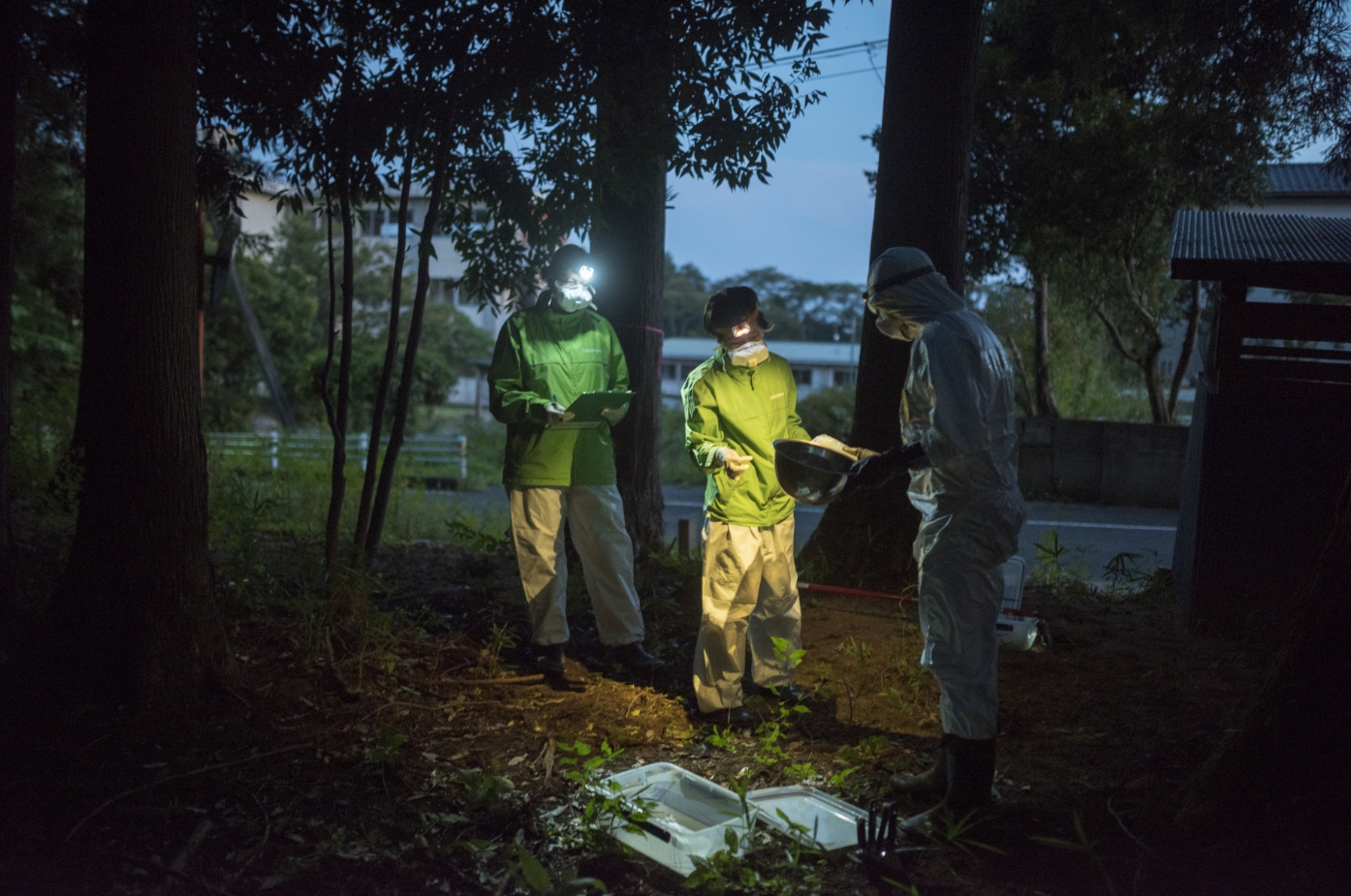

Geographic features result in what are referred to as ‘hotspots’, where the movement of soil and water causes localised spikes in radiation levels. In many cases, the Greenpeace surveys have revealed high levels of contamination in forested areas and unexpected hotspots that would otherwise go unrecorded. Suzuki has often wondered what the results mean for individuals living in the surveyed areas.

“In the period soon after the nuclear accident, local residents who cooperated with our surveys would often ask us our opinion on what they should do. At that time, they were often desperate and clutching at straws. There was a real lack of information. All we could do was to share our results with them and advise them of the possible risks. Of course, the precise figures are important, but knowing what advice to give people facing this upheaval in their lives was the hardest part of the work.”

Knowing the exact levels of contamination can be helpful when making decisions on how to minimise exposure risks or whether or not to evacuate, but sometimes the figures drive home the painful truth that one’s hometown is no longer a suitable environment to return to.

Treading on stolen lives

“Many people have allowed us access to their homes for surveying, but when I imagine the lives that by rights they should have been living there, I find myself welling up with emotion. I have to focus on my measurements and try to put my feelings to one side.”

When carrying out surveys within the government-mandated evacuation areas, the team accompanies evacuees to their former homes, and asks them to describe their day-to-day life there. This helps the team to put together a picture of how the house was used, and which in turn they use to plan the survey method. However, the process takes an emotional toll, “It feels like an interrogation, asking people to describe a lifestyle that’s been stolen from them,” says Suzuki.

“We ask people to describe their daily life in great detail - what each room was used for, how many people lived there, what vegetables they grew in the garden, what shoots and berries they collected from the hillside behind the house, and so on. To measure the radiation on the ground, we often have to push our way through weeds that tower above our heads. It’s sobering to think that those dense tangles of weeds are growing through what may have been someone’s vegetable patch, or that I may be placing my feet on what was once a carefully-tended flowerbed.”

At the end of a day’s surveying, as they head back out of the evacuation zone, Suzuki and her team pass through deserted villages where the houses stand dark and empty, no smell of cooking wafting out into the streets. It is a stark reminder of the circumstances that suddenly stripped these communities of life.

How contamination travels from the ocean to the dining table

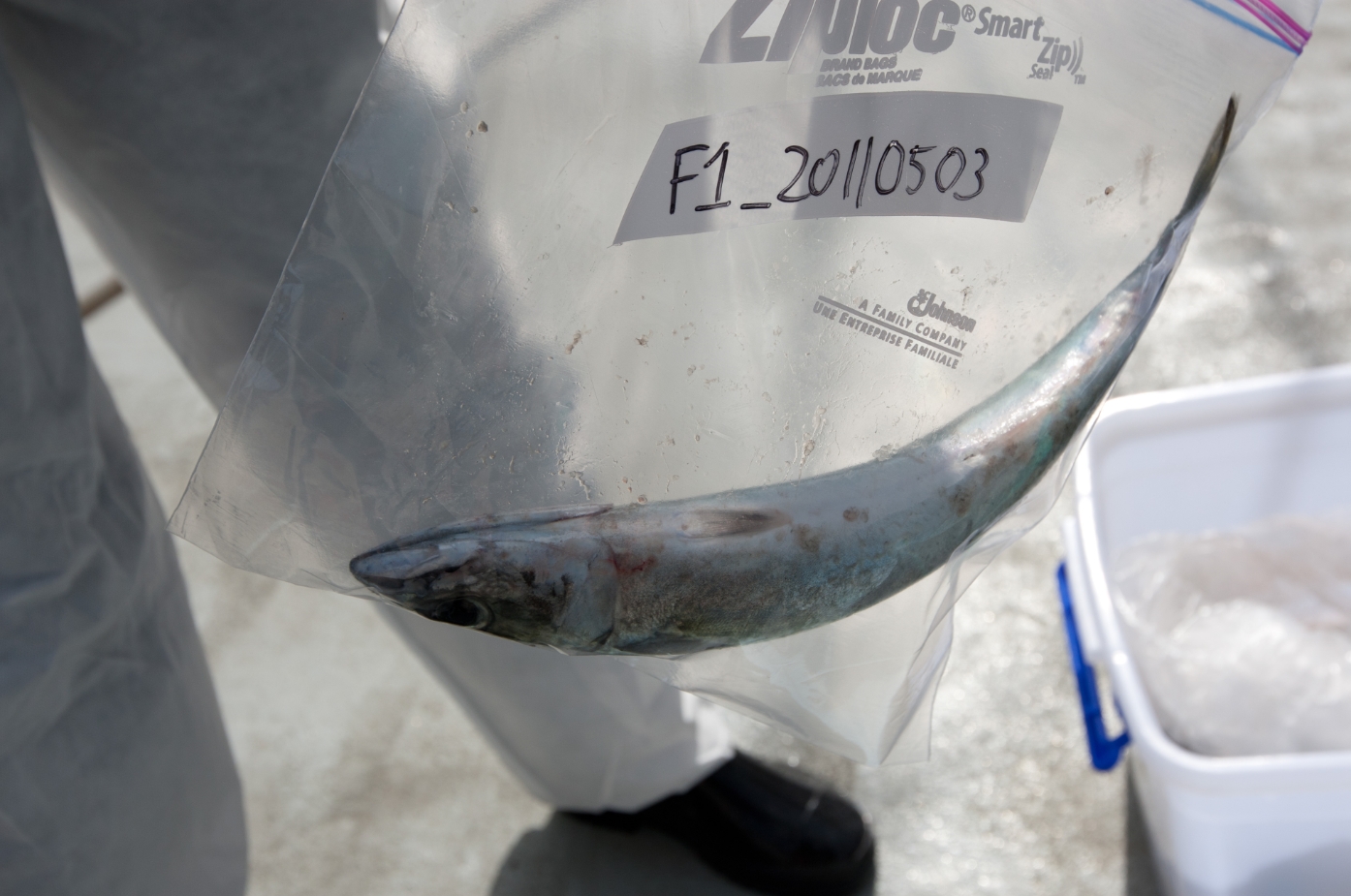

In October 2011, Greenpeace started an independent investigation in an attempt to ascertain the true scale of radioactive contamination in food. They opened a radiation testing laboratory, ‘Shiru-beku’ in Tokyo, where Suzuki also worked. Shiru-beku had a particular focus on seafood, an important part of the Japanese diet. They released their findings with the assistance of third-party measurement experts. The Chernobyl disaster, which was rated on the same scale as the accident at Fukushima Daiichi, occurred far inland, so the emissions into the Pacific Ocean that occurred in Fukushima were on an unprecedented scale. The build-up of radioactive particles in the ocean ecosystem was a major concern, and unlike farmed vegetables, posed major challenges in terms of traceability.

Initially, the team purchased and tested seafood in the Kanto region (Greater Tokyo and the surrounding prefectures), but they needed to source samples from a wider area. With the help of volunteers recruited from up and down the country, they were able to test samples from the north and west regions of Japan. Some volunteers who took part from Fukushima prefecture assisted with the investigation as a way of addressing their own concerns, saying that there was nobody else with whom they were able to discuss the risks posed by radiation.

“The cooperation of these citizen volunteers made a lasting impression on me,” says Suzuki, “it wasn’t a simple matter of buying any old fish and sending it over – we were asking them to go to a particular retailer and buy at least 500g of a particular cut of a particular fish caught in a specified region. If that fish was out of stock on a particular day, or they couldn’t get the required amount, they would go back to the same place the next day. Some of our volunteers would even go to different branches of the same chain until they found what they were looking for. At the time, there was a lot of conflicting information flying around, and there was a lot of public fear surrounding contamination finding its way into the food supply. The project allowed us to share the importance of taking these measurements with a lot of people.”

Immediately after the accident, the Japanese government set a guideline of 500 Bq/kg (Becquerels per kilogram) as an ‘interim standard’ for food products, but a year later the level deemed acceptable for general food, including meat and fish, was dropped to 100 Bq/kg. Although the government ran a screening program for seafood products, it was never realistic to screen every single fish in the supply chain to ensure they were under the threshold. Of course, no test results were provided on the packaging. Shiru-beku’s seafood testing aimed to encourage retailers to take responsibility for ensuring safety and quality, by prompting supermarkets to take the initiative by arranging their own inspections and applying reasonable standards. Involving retailers in the process of ensuring consumer confidence served not only to minimise the risks of internal radiation exposure, but was also key to supporting the producers and thus assisting with the recovery of the fishing industry.

“During the period of this survey, which we ran from 2011 until 2013, visible radiation readings came from fish caught comparatively close to the Fukushima Daiichi plant, specifically off the Sanriku coast in north-east Japan and also off the coast of Chiba prefecture. However, even though we knew about the migratory habits of fish, we were still surprised when we saw elevated readings coming from the more distant fisheries of Hokkaido, Shizuoka, and Hyogo prefectures**. Not only that, but we detected radiation in farmed fish from Kagoshima prefecture (in Kyushu) and in processed canned fish. This demonstrated some of the complex routes by which contamination was finding its way onto the dining table, for example via contaminated fish food and the distribution networks of the processed seafood industry.”

Although contaminated water from the Fukushima Daiichi site has been trickling into the ocean since the time of the disaster, in 2020 the Japanese government published a report declaring that the most ‘realistic’ option for disposing of the massive quantity of water collected in storage tanks at the plant will be to dump the water in the Pacific Ocean. The levels of cesium in seafood have been steadily dropping, to the extent that contamination exceeding the permitted limits is no longer being detected. Just as signs of recovery are starting to appear, this move by the government would be a devastating new blow to the fishing community, who are vehemently opposed to the plans.

Milestones are a matter of perspective

Suzuki remembers a conversation she had about the approaching ‘milestone’ of the fifth anniversary of the disaster with a resident in the village of Iitate, when working on a survey in late 2015.

“I remember one elderly farmer very gently said to me, ‘Five years may have passed but that’s neither here nor there. It’s all the same to me.’ I think what he wanted to say was that when you are struggling with the same problems day after day with no resolution in sight, it’s difficult to accept a ‘milestone’ as having any particular significance. It’s just a number.”

For the people caught up in the events of that day, the anniversary of the earthquake on March 11th is just one more day in the calendar that comes and goes like any other. The obsession with counting the years is the preserve of those who watch from a distance.

Suzuki was motivated to get involved in radiation surveys out of a desire to uncover first-hand the reality of what was happening in Fukushima and Japan as a whole. Sometimes she feels what she is able to contribute is declining by the year.

“Carrying on is not as easy as it sounds. I think part of the problem is I am just so weary of the situation now, I feel I have less and less to offer. But if we are to prevent a repeat of what happened in Fukushima, I have to figure out what I can do, and force myself to stick with it. Maybe, the dividing of time into milestones and anniversaries is more important for us than for the people living in Fukushima, because it provides us with a chance to remember and reflect.”

- *Gamma ray spectrum measurements taken using a germanium detector. Measured isotopes are cesium 134 and 137, and iodine 131. Detection threshold of each is less than 5 Bq/kg.

- **Distances from Fukushima Daiichi site: Hokkaido approx. 650 km, Hyogo approx. 590 km, Shizuoka approx. 400 km, Kagoshima approx. 1000 km.