“If they had been able to carry on searching that day, it’s just possible that my daughter might have been saved. There’s no way of escaping the fact that it was the nuclear accident that forced them to call off the search.”

scroll

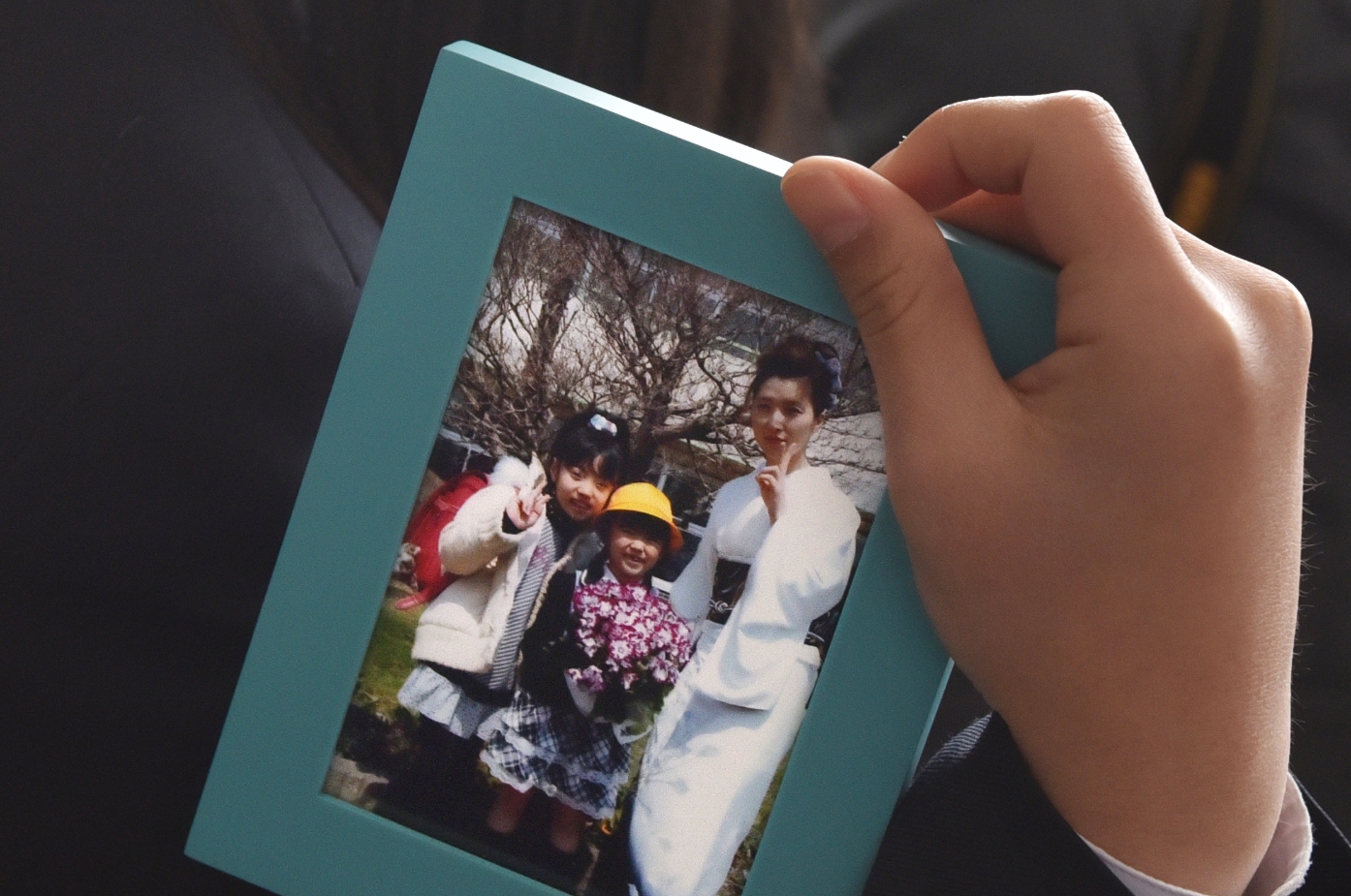

- ProfileNorio Kimura

- Norio Kimura lived in the town of Okuma, Fukushima prefecture, at the time of the disaster. He has been living the life of an evacuee ever since; in Nagano prefecture until 2019, and now based in the city of Iwaki, Fukushima. His former home by the sea is now the site of an intermediate storage facility for nuclear decontamination waste, in an area officially designated as “difficult-to-return.” However, Kimura continues to return to Okuma in order to search for his second daughter, Yuna, who went missing in the tsunami.

The 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake and tsunami left over 20,000 people either dead or unaccounted for. Although the earthquake was one of the most powerful on record, it is now believed that 92% of the victims were actually claimed by the ensuing tsunami. This tidal wave inundated Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant, resulting in a loss of cooling ability that caused the reactor cores to fail one after another in a series of explosions. Already overwhelmed by the catastrophic damage caused directly by the earthquake and tsunami, the authorities were stretched thin in their response to the nuclear crisis unfolding at Fukushima Daiichi. The high radiation levels from Fukushima brought extra challenges, frustrating what was already an unforgiving task in the natural disaster crisis response, and delaying the search and rescue operation.

Killed by the tsunami, or left to die?

At the time of the earthquake, Norio Kimura was living three kilometres from the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant in Okuma town. After the tsunami tore through the area, Kimura was still searching for his missing family when, on March 12th, the order was given to evacuate a 10 kilometre radius around the stricken power plant. Along with his mother and eldest daughter, who were unharmed, he was forced to leave Okuma behind. In the ensuing period, and in hope of finding clues as to the whereabouts of his missing remaining family, and hampered by the fact that the entire town was located within the danger zone, closed even to its residents, Kimura resorted to handing out leaflets at evacuation centres in and around Fukushima prefecture. The bodies of his father and wife were found in April, but his second daughter Yuna, who was 7 years old at the time, remained missing. At the end of May, Japan’s Self-Defense Force finally began searching in the danger zone, but even they found nothing.

Although Kimura is now permitted to spend up to 30 days a year in Okuma, in the years immediately after the disaster when the evacuation order remained in place, visits to the town were limited to a maximum of two hours, once every three months. On each occasion, Kimura would make the 450 kilometre journey from Nagano prefecture, where he was living as an evacuee, don protective clothing, and use the precious little time allowed him to walk through the rubble searching for his missing daughter.

As time passed, volunteers began joining Kimura in his search, however, even with their added help, it was impossible to sort through the piles of debris using only hand tools. After a search team from the Ministry of Environment joined their efforts in December 2016, Yuna’s partial remains were discovered not far from the site of Kimura’s home. All that was found were a few fragments of neck bone buried in the rubble, still wrapped in a child’s pink Minnie Mouse scarf, stained brown from the years spent lying in the earth. DNA testing later confirmed the remains to be those of Yuna. Six years had passed since she had gone missing.

After his daughter’s remains were found, Kimura began to experience a fresh rage. Knowing the location where Yuna’s remains were found, he started to wonder whether she might have initially survived the tsunami, but then died after being abandoned when everyone was forced to evacuate.

“The local fire department volunteers were searching the area right up until the evacuation order came through on March 12th”, he says.“They confirmed that they could hear a human voice. Yuna was found nearby, which means it could have been her or my father that they were hearing. If they had been able to carry on searching that day, it’s just possible that my daughter might have been saved. There’s no way of escaping the fact that it was the nuclear accident that forced them to call off the search.”

Under a growing pile of contaminated earth

Soil and contaminated waste generated by the decontamination work in Fukushima prefecture is being held at intermediate storage facilities while awaiting permanent disposal. Kimura’s former home is located on the southern edge of one such facility, a site which alone covers 16 square kilometres within the “difficult-to-return” areas of Okuma and neighbouring Futaba.

Back in 2014, this land was bought up by the government, who held meetings with residents to explain the construction of the intermediate storage facility.

“I told them I couldn’t give my support to the project. To start with, the Ministry of Environment wasn’t even aware of the possibility that victims were still lying undiscovered in the area. I just couldn’t believe they’d come to lecture us without even bothering to check something like that.”

Kimura had lost faith in the government response and turned down repeated requests from the Ministry to allow them to search for Yuna and others in order to allow the construction project to progress, and was also unhappy about the rows of heavy-duty waste bags now piling up across his old neighbourhood. However, due to the strength of his desire to find Yuna and wish to provide closure for the volunteers who had helped him, he ultimately agreed to let the Ministry of Environment search. As an individual it was impossible to bring in heavy machinery, but a government-led search made this possible, and finally led to the discovery of Yuna’s partial remains.

The site of Kimura’s former home is now lost, covered by the waste storage facility. However, he says the spot where Yuna’s bones were found has been left undeveloped and although he continues to search for the rest of his daughter’s remains, when he looks at this one untouched spot, Kimura has come to wonder whether the fact that he has been unable to find her entire body might not have its own significance.

“I’ve started to think that even if we don’t find the rest of her, as long as they leave that spot alone, it serves as a kind of memorial. I know Yuna is still somewhere in there, but if we find the rest of her, that would be the end of it - there would be no reason to keep that spot intact. It’s almost as if Yuna is keeping herself hidden, to make sure that what happened here isn’t forgotten.”

Five years ago, Kimura started planting wild rapeseed and sunflowers to bring a bit of colour to this lonely spot. When the flowers bloom, the site is carpeted in yellow, and he talks of adding cotton and mulberry plants to the mix in the future.

Who really drives nuclear power?

At an event a couple of years ago, Kimura heard the head of Tokyo Electric Power Company (TEPCO) comment that “Electricity production safeguards our lives”. On hearing this, he started to reassess the role of individual consumers in the electricity industry.

“It shook me up. Is it possible that TEPCO, in trying to “safeguard our lives”, could have cost my daughter her life? I’ve come to realise that at the end of the day, it’s us, the consumers, that let TEPCO get away with saying something like that. As much as TEPCO might be to blame (for Fukushima Daiichi), without a more fundamental change in society, we won’t make progress. It’s clear to me that nuclear plants shouldn’t be restarted, but at the same time, it’s our appetite for electricity, rather than TEPCO, that drives the demand to go back to nuclear.”

The power companies have encouraged us to treat electricity as if it were an unlimited resource, and nuclear power has grown to keep up with the burgeoning demand. Kimura believes that ending nuclear power will remain a distant goal unless we do more as individuals to rethink our excessive consumption and start shifting to more energy-conscious lifestyles.

“As far as the intermediate storage facility goes, I appreciate that it makes sense to put it near the power plant site. But at the end of the day that was my hometown, and I’m not happy about it. Part of me even feels like saying ‘If you’re going to use their electricity, bury the mess in your own damn garden!’”

Kimura wants to spread his message that disaster prevention, the nuclear accident and radioactive contamination, and also our day-to-day consumption of electricity affect us all personally, and hopes that by sharing his personal experiences, that one day he may just save a life.

No more lives that “should have” been saved

Five kilometres inland from Kimura’s former home lies Futaba hospital where, at the time of the disaster, high radiation levels hampered rescue and evacuation efforts by the Self-Defense Force, leading to delays that resulted in the deaths of 44 patients either en-route or after arrival at the evacuation centre. At the time, the deputy chief nurse at Futaba hospital testified that “Despite the devastation at the hospital, more people could have been saved (without the added complication of the nuclear accident)”.

Lives that could and should have been saved in the aftermath of the earthquake and tsunami slipped away unseen. The very presence of nuclear power has the potential to exacerbate crises brought on by natural disasters (earthquake, tsunami, rain, snow, or volcanic eruption), terrorism, or even more relevant today, epidemic. Radiological accidents are an avoidable, man-made tragedy, and if we learn from what the people of Okuma have been through, our individual choices may allow us to start heading toward a future where no more lives that “should have” been saved are lost.