“I’ve met a child who has told me that they would keep quiet even if they developed thyroid cancer because they worry about causing reputational damage that could hurt Fukushima’s agricultural economy. “

scroll

- ProfileMari Suzuki

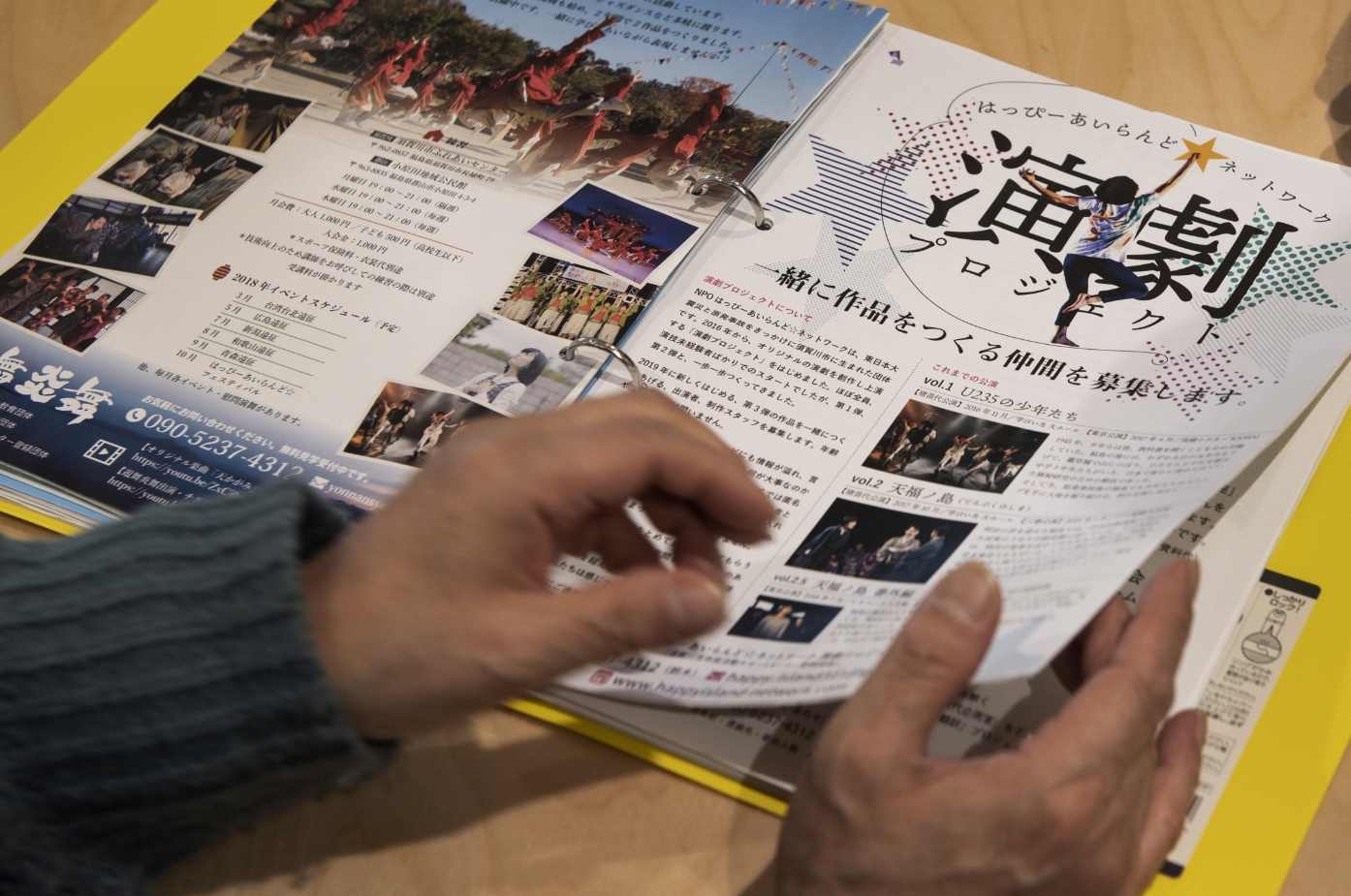

- In May 2011, Mari Suzuki got together with friends to set up the non-profit group "Happy Island Network" in the city of Sukagawa, Fukushima prefecture. She has been acting as their spokesperson since 2012. The group’s activities are many and varied, ranging from seminars, workshops, and health consultations, through to dance and theatrical performances, but are all centered on the same motif: "Looking life in Fukushima in the eye; facing the present, and thinking about the future."

In the early days after the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake and tsunami, the non-profit group Happy Island Network (hereafter Happy Island) based in the city of Sukagawa focused on the distribution of disaster relief supplies. As they evolved and diversified, in 2012 the group adopted the motto “Looking life in Fukushima in the eye; facing the present, and thinking about the future”, a concept that serves as a common thread running through their various programs. Their strategy is to use cultural activities as a soft medium, creating an environment that makes it easy for participants to engage and get to know one another, whilst gently raising awareness.

The importance of facing up to reality

“We’re a loosely structured and non-hierarchical network, with a fluid membership. Some of our older members have moved away, whilst new members have joined,” explains Happy Island’s spokesperson, Mari Suzuki.

With the assistance of medical professionals, Happy Island organise health consultation sessions where people can freely discuss their questions and concerns about radiation. The group also arranges retreats to allow children who have not been able to evacuate to spend some time away from contaminated areas in a stress-free environment. Through such schemes, Happy Island hopes to take care of not only the physical, but also psychological, health of Fukushima residents. Every month the group holds coffee mornings, providing a relaxed setting where local mothers can come together get the latest information on contamination levels and discuss the concerns that come with bringing up a child in Fukushima.

However, at the core of Happy Island’s work is theatre – something that might at first sound rather tangential to the group’s remit. But as Suzuki explains, Fukushima residents live day-by-day with a vague yet persistent sense of unease and anxiety. The ability to think things through clearly is vital if one is to find a way out of this cycle of unease and anxiety – and in Suzuki’s view, theatre is the perfect medium for training people to “think” properly.

“If the state is trying to coerce you into accepting an unfair situation, unless you fully appreciate your own position you will never be able to stand up for yourself. If you let life carry you passively along, there are very few opportunities to develop your own sense of conviction to the point where you become able to speak up and act on your beliefs. We thought that if theatre could serve as a stimulus for studying, critical thinking, and comprehending, this could help teach people the skills they need to fight back against such unfairness.”

Happy Island’s first theatrical project was a piece entitled “The U235 Boys” based on the true story of junior high students from Fukushima who were enlisted as student workers to mine uranium for the Japanese atomic bomb program during World War 2. The play draws parallels between the war and nuclear power as two national projects that have brought chaos into the lives of young people living in different eras. Not all of Happy Island’s plays address the issue of nuclear power directly. In 2018 the group put on “Tenpuku Island” dealing with the People’s Rights Movement in Fukushima of 1882, and their 2019 effort dealt with themes of mutual hatred and understanding, through a story about the lives of ethnic Koreans in Japan.

A new cast is recruited from young people from their teens to thirties for each new play the group produces. Although some have acting experience, for the majority it is their first taste of theatre. As Suzuki explains, very few participants come professing an interest in the themes of the plays or critical thinking when they first join the group.

“We welcome anyone, whether they just want something to do with their friends or think it might be good fun. There’s no need to think too hard to start with – that’s something you learn on the way. Part of the process of putting together a play is learning about the history and background. With that process comes the realization that ‘These are things that actually happened!’. Whether you’re part of the cast or the audience, your understanding gradually changes as you start to put yourself in the position of the characters in the story, and it becomes something relevant to yourself.”

A change of perspective means a change in perception

“One of our plays featured heavy-duty black sacks, the same sort that are filled with contaminated soil from the nuclear decontamination. One of the girls in the cast was a teenager who had never made the connection between the nuclear disaster and the black sacks she saw piled up around her hometown. Afterwards she began seeing these sacks in a new light, and came to understand their perverse significance in the landscape.”

Those who were still very young at the time of the Fukushima Daiichi accident have grown up against a backdrop of disaster for as long as they can remember. Theatre can serve as a visual wake-up call, explains Saaya Ono, who oversees scripts and acting. Ono herself was 18 at the time of the earthquake.

One of the lines in “Tenpuku Island” is “The worst part when someone steals something you can’t see, is that you don’t even notice.” The line is inspired by an actual speech given by Iwamatsu Kotoda, a young activist in the Fukushima People’s Rights movement, who said “There will always be thieves who will rob you of money and tangible assets, but what is truly unacceptable is when the people in power rob us of our intangible assets, our rights”.

Although a problem may be staring us in the face, as time passes it becomes harder to see it clearly, and thus harder to talk about. The waste sacks are just one tangible example of a situation where a little knowledge can change the way something appears. But the same is true for our “rights”, which despite having no physical shape, can still be eroded little by little every day. Theatre can act as a catalyst that enables us to recognise these abstract ideas more clearly.

“Stories about the past provide us with the imagination to look at ourselves and others living in the present. I believe that changing and broadening our own perspective allows us to revisit our own ideas of how we should live,” says Ono.

Understanding a situation is key to discussion

As the young people who get involved in Happy Island’s theatre projects go on to become fully-fledged members of society, inevitably some move away from the area and lose contact. That’s fine, reflects Suzuki philosophically.

“Wherever those young people end up, when the topic of Fukushima comes up in conversation, if their experiences with the theatre group have taught them the ability to look closely at reality and think critically, perhaps they will be able to express themselves more articulately than just with a clichéd ‘Fukushima sob story’. I hope so, in any case.”

As well as exploiting the two-way interaction between critical thinking and expression in their drama projects, Happy Island also takes a more direct approach toward training people to think critically in their “Literacy Workshops.” Participants are encouraged to think about how to digest the information that reaches them through the media. These workshops attract participants of all ages, ranging from elementary school students, through university students, all the way to the elderly. They look at newspaper cuttings from articles about Fukushima, and discuss what message is being presented, what’s being left out, and if anything doesn’t feel quite right.

We live in an age overflowing with information, whether it be from television or the internet, and separating truth from fiction and identifying what is important is not always an easy task. In particular, in the immediate aftermath of the Great East Japan Earthquake, often emotions took precedence over careful analysis.

Happy Island run a festival, “Happy-Fes”, which includes a “talking café” where people of all backgrounds can share their experiences. Among a number of young adults who were still at elementary school when the earthquake struck, one visibly upset participant asked “Why is it that there is so much we don’t know? If we don’t know the full story of what happened, how are we supposed to be able to protect the people important to us next time?”. Suzuki realised there is a need for adults to help bridge this knowledge gap.

Why are children being stopped from speaking up?

Suzuki also has concerns over the effect the language and behaviour of adults has on their children.

In December 2020, Suzuki and others prepared and submitted a written opinion calling on Fukushima prefecture to continue its in-school thyroid screening program. These thyroid screenings were introduced by the prefectural government with the stated goal of closely monitoring the health of Fukushima citizens until 30 years have passed since the Fukushima Daiichi disaster. Specifically, screening at schools was brought in in order to allow equal access to anyone who wants to use the service. However, a committee set up to review the health monitoring program are currently considering whether or not to continue with the in-school screenings. Their reasons for ending the program include the fact that holding the screenings in schools can create the impression among parents that the screenings are compulsory, and that the schools are tired of hosting the screening sessions. By contrast, Suzuki takes the view that easy access to screenings should be a right of the children who have been involuntarily exposed to radiation. However, she says many people she speaks to don’t seem to be troubled by these new developments.

“I get the impression that a lot of people don’t want to be seen to be disagreeing with the authorities because of the unseen pressure not to make a fuss and risk further reputational damage. I’ve met a child who has told me that they would keep quiet even if they developed thyroid cancer because they worry about causing reputational damage that could hurt Fukushima’s agricultural economy. It’s the adults in society that are placing pressure on youngsters to keep quiet, even if they are suffering. As adults, if, God forbid, health complications did arise, it should be our job to pursue those responsible, rather than fretting about reputational damage.”

Children are very conscious of the behaviour of adults in the way they choose their words. You sometimes hear the phrase “anti-Fukushima discrimination” – but it is adults who create discrimination, not children.

“If we really mean to prevent the spread of discrimination, we need to face up to reality and speak openly rather than beating about the bush. Unless we do that, I don’t believe discrimination will ever go away.”

Don’t be complacent about the current situation

As the 10th anniversary of the Fukushima Daiichi accident approaches, Happy Island are hosting a series of talks entitled “Take a stand against ‘’recovery by resignation”. Participants are invited to hold discussions with each other after listening to what the speakers have to say.

In the last few years, evacuees have found themselves under pressure to return to Fukushima, and in 2020 evacuation orders were lifted for the first time in certain areas that had previously been categorised as “difficult-to-return.” The Tokyo Olympics and Paralympics are being touted as the “Recovery Olympics,” promoted by relentlessly upbeat news coverage. Meanwhile, the people of Fukushima keep their true feelings to themselves, repeating the mantra “there’s nothing I can do about it.” Suzuki calls this shift in society that effectively encourages the victims of disaster to accept their situation as ‘recovery by resignation’, and says she hopes to enter the second decade of the Fukushima Daiichi disaster fighting back against this complacency.

For the people of Fukushima, it is not easy to objectively assess one’s situation while living through the reality of the disaster and the continuing challenges of living in the region. There are no easy decisions and not necessarily any right answers. However, unless people make the effort to critically engage, the facts of the disaster will weather and erode. Meanwhile, Suzuki and her colleagues at Happy Island continue in their quest to provide flexible environments that gently prompt people to develop the critical thinking skills that will help them to look for their own answers and connect with other people - while dancing, singing, and performing on the way!