“The Japanese constitution states ‘We recognise that all peoples of the world have the right to live in peace, free from fear and want.’ However, the Japanese government has failed in its duty to protect citizens, and instead puts all its efforts into pressuring evacuees to return to Fukushima.”

scroll

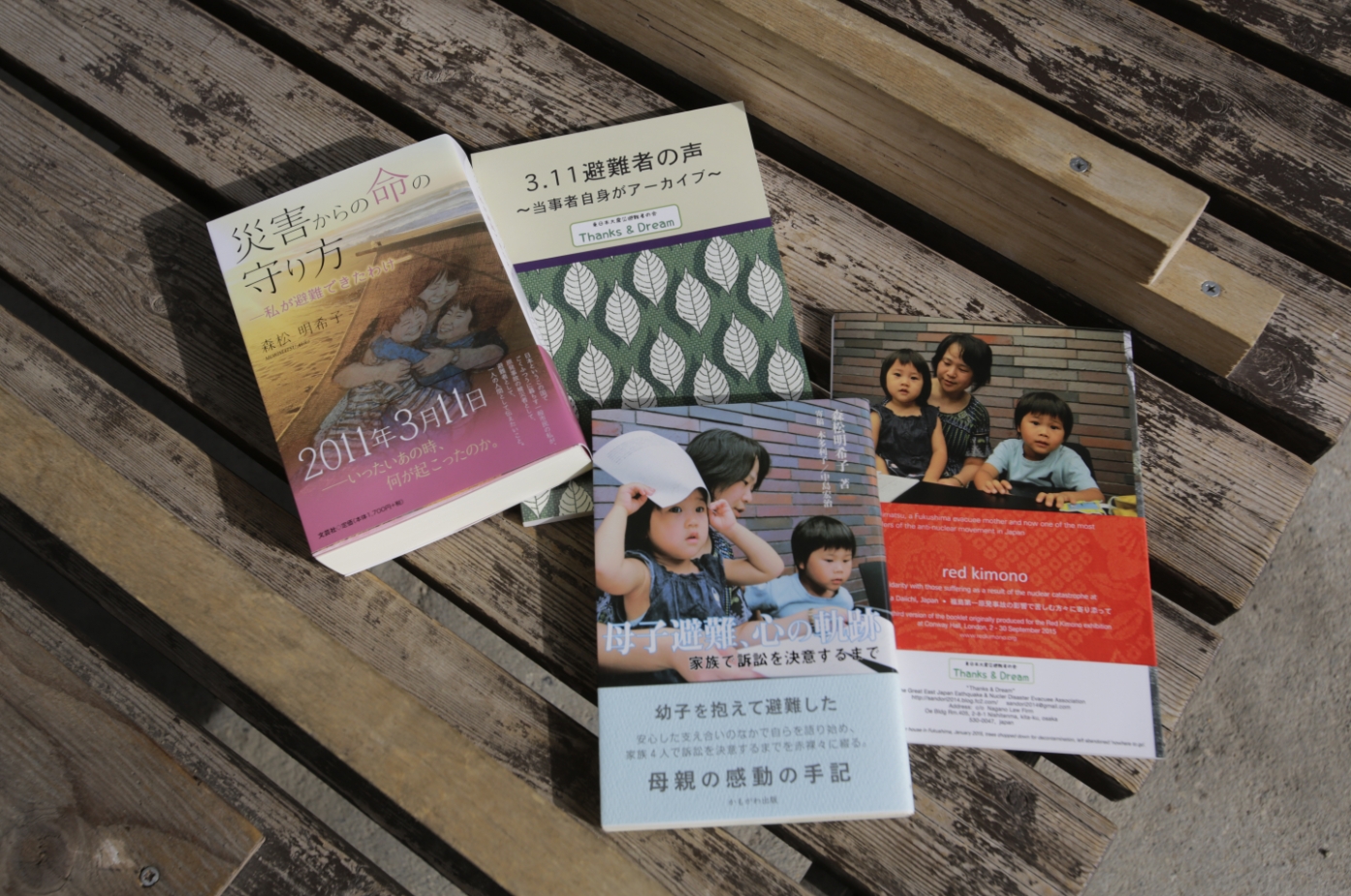

- ProfileAkiko Morimatsu

- Two months after the nuclear accident at Fukushima Daiichi, Akiko Morimatsu made the decision to leave her home in Koriyama, Fukushima prefecture, taking her two young children to Osaka. She now leads “Thanks & Dream”, a group for evacuees of the Great East Japan Earthquake, and is also a representative of a Kansai-based class action seeking compensation for the victims of the nuclear accident. She has become an ardent campaigner for the rights of evacuees, and speaks on the subject both inside and outside Japan.

Following the Great East Japan Earthquake in March 2011, more evacuees fled Fukushima than any other prefecture. Over half of Fukushima’s evacuees were displaced as a direct result of the nuclear accident at the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant. By September 2011, the number of Fukushima citizens living as evacuees was around 150,000. After peaking at around 160,000 in 2012, the total has been gradually declining; however, as of 2020, at least 45,000 people are yet to return home.

Those who left their homes following the radioactive releases at Fukushima Daiichi can be broadly split into two groups: ‘forced evacuees’ from areas officially deemed unsafe by the government, and ‘voluntary evacuees’ from outside these areas who nonetheless made the decision to leave. Statistics for September 2011 tell us that of the total population of 150,000 who left the area, around two-thirds were ‘forced’, and the remaining one-third were so-called ‘voluntary evacuees’. Although the number of people who left voluntarily is estimated to be around 15,000 in recent years, the exact number is unknown and has not been formally ascertained. It is possible that the true figure is much higher than the official data suggests.

Faced with a difficult decision

“After the accident, the communities closest to the plant started to be evacuated first. I assumed the government would then start issuing evacuation orders* for areas further inland according to how bad the radiation levels were. So I waited and waited, but no order came through.”

At the time of the disaster, Morimatsu lived with her family of four in the city of Koriyama, about 60 km west of the Fukushima Daiichi plant. One day in the first few weeks following the disaster, the Japanese government banned the sale of leaf vegetables from Fukushima prefecture after radiation levels exceeding the permitted limits were detected. The following day, Morimatsu was shocked by the news that a cabbage farmer in neighbouring Sukagawa had taken his own life. Although she was worried about the risk of contamination in her local area, Morimatsu was unable to come to a firm decision about what she should do, and in April 2011 she enrolled her oldest son in a nearby kindergarten as planned. At the start of term, however, she discovered that a third of the families had already withdrawn their children.

“At the kindergarten, the children were forbidden from playing outside to protect them from radiation exposure. Every week, I saw more and more families moving out of the area. Despite this, there was no reliable information available about the real level of contamination. Is it safe to stay here, or are all the people who have left just panicking about nothing? If things got that bad, the authorities would be in touch, wouldn’t they? Every day, my head was full of these unanswered questions.”

After agonizing deliberation, two months after the accident Morimatsu took her two young children, then aged 0 and 3 years old, and left for the Kansai region where she grew up. She was forced to leave behind her husband, whose job required him to stay in Koriyama. Considering the potential risks to her children, she believes the decision was unavoidable.

Among the ‘voluntary evacuees’ from Fukushima, mother-and-child units such as Morimatsu and her children are particularly prevalent. Those who left on their own initiative often feel a sense of guilt when they consider their in-laws or other mothers who have chosen to remain in Fukushima.

Divided by those responsible

‘Voluntary evacuees’ such as Morimatsu face their own unique hardships within the evacuee community. Families living apart typically have two sets of living expenses, not to mention the additional financial burden of traveling in order to get together, but are entitled to little financial support. Add to this the emotional burden of being unable to spend time together as a family and uncertainty over the future, and the challenges can quickly become overwhelming. These issues continue to affect the community to this day, and make life for those who chose to leave difficult to sustain.

As an evacuee, whether or not your evacuation has the government “seal of approval” greatly affects your status. Although all the evacuees share a common story, that of having been uprooted due to the dangerous release of radiation from Fukushima Daiichi, those labeled ‘voluntary evacuees’ often find themselves treated as if they are less entitled to assistance due to acting on their own initiative. They suffer discrimination not only in the wider community, but also from other evacuees. There are stories of families being torn apart by disagreements over whether to leave or remain. Women and children living away from Fukushima are often dependent on financial support from the father. If the father becomes unwilling to send money, a life in a new area quickly becomes impossible to sustain. No wonder, then, that many evacuees struggle with financial hardship.

“Any evacuee that isn’t from the government-mandated area is labeled a ‘voluntary.’ I think this categorisation creates the impression that evacuation for them is a luxury and their situation is therefore their own responsibility. The irony is that these categorisations were invented by the same people that bear responsibility for the accident in the first place - the Japanese government and TEPCO.”

Forgetting we have rights

Morimatsu found herself unable to dispel an increasing sense of unease over the segregation and prejudices that were pushing the victims of the disaster apart. Individual circumstances were driving rifts through the community. The ‘forced’ or ‘voluntary’ nature of evacuation, the level of compensation received, and personal factors affecting families’ decisions to stay or leave had all become divisive issues. The absurdity of this situation struck Morimatsu.

“At evacuee support meetings, I often hear things like ‘Plenty of people have it worse, so I shouldn’t complain’, or ‘I’m really struggling, but so-and-so has it easy.’ Even though we’re all in this together, we can’t help but compare our woes. When we should be pursuing the government and power industry, instead we find ourselves venting our frustrations on one another. I think this comes from a culture of forgetting about our own rights. But that got me thinking - what exactly are our rights?”

One day, Morimatsu found what she was looking for: a passage in the UN’s international guidelines concerning the Guiding Principles on Internal Displacement. Surely, evacuees from the Fukushima Daiichi disaster qualified as “internally displaced persons” and are therefore entitled to protection? Escaping radioactive contamination for the sake of their health was a fundamental human right – one that was being violated on a daily basis. Nobody should be forced to live in fear of developing an illness. Suddenly everything became clear to her.

“Some people say that unlike forced evacuees, we’re free to go home whenever we want to. Voluntary evacuees aren’t properly recognized, either by the government or by the rest of the community. This drove me to find proof that my course of action was justified. I found this proof in the ‘right to enjoy a normal standard of health.’ I believe if we come to understand that we are all united by our human rights, we could start to bridge the divides that split us as evacuees. Each of us has an equally valid right to protest against the hardships of our personal circumstances.”

Morimatsu is keen to emphasise that she isn’t blaming anyone for their lack of awareness of human rights. She sees it as a problem that pervades society, a result of government policy and the education system. Japanese society has tended to favour social harmony over individual rights, and in her view, the pressure to conform has reached pathological proportions.

After learning about the human rights that should be guaranteed for anyone caught up in a disaster, Morimatsu began working to spread awareness of victim and evacuee rights. In 2013, she took on the role of representative for a class action legal case brought by Fukushima evacuees living in the Kansai region, launching a legal campaign demanding compensation and damages from TEPCO and the Japanese government. In 2014, she formed the evacuee support network “Thanks & Dream”, which shares information through the internet and group meetings. In order to develop a support framework tailored to the requirements of long-term evacuees, Morimatsu believes it is necessary for those affected to speak up about their circumstances and needs. She feels that Thanks & Dream’s activities, as well as the legal case, have helped to advance the public’s understanding of the plight of the voluntary evacuees.

Vanishing evacuees and their changing status

In March 2017, the Japanese government ended the provision of free housing for voluntary evacuees. This resulted in a large number of those that left Fukushima being forced to return against their wishes, unable to meet the financial challenge of renting accommodation whilst also keeping up mortgage payments on their Fukushima homes. Fukushima prefecture announced that it would provide financial support to those willing to return. This marked a turning point in official policy, which shifted toward cajoling people to return home in an attempt to reduce the number of evacuees. Evacuation orders were withdrawn in some areas and compensation schemes were ended, putting pressure on even ‘forced’ evacuees to return.

However, even after scaling back evacuation orders, the number of those willing to return was fewer than expected, prompting the government to announce a new policy in late 2020 of paying up to 2 million yen (about 20,000 USD) to anyone prepared to move into the towns and villages surrounding Fukushima Daiichi. Funded by taxpayers’ money, the focus of this scheme is not to allay the public’s concerns, but to artificially create ‘recovered communities.’

“It doesn’t make sense that those who bear responsibility for the disaster are the ones now deciding to cut off compensation and roll back the evacuation orders. They co-opt the voices of evacuees who say they wish they could go home but are unable to, into a message of ‘We’ve opened up your town again, so please go home now.’ In reality, hardly anyone is returning to the most contaminated areas. What happens instead is that people who were formerly classed as ‘forced evacuees’ are now becoming ‘voluntary evacuees.’ Paradoxically, one result of this shift is that now, forced ones and voluntary ones alike are able to come together in protest at the inadequate support offered by the government.”

As time passes, Morimatsu feels that the emotional barriers dividing the victims of the Fukushima Daiichi disaster have started to break down. Where there was once misplaced resentment, people are now coming to understand and respect one another’s choices. The victims of the disaster are coming to recognise the importance of working together, irrespective of their individual circumstances and choices, bound by the common thread of their shared human rights.

In 2018, Morimatsu traveled to the UN Human Rights Council in Geneva as a representative of the victims of the Fukushima Daiichi disaster. In a speech to the council, she said “the Japanese constitution states ‘We recognize that all peoples of the world have the right to live in peace, free from fear and want.’ However, the Japanese government has failed in its duty to protect citizens, and instead puts all its efforts into pressuring evacuees to return to Fukushima.” The Japanese government has claimed that it will work on the recommendations of the UN Human Rights Council, but so far, there has been little appreciable progress in developing a legal framework to protect the human rights of disaster victims.

Passing the baton of human rights to the younger generation

Some people deliberately hide their evacuee status, or gloss over their evacuee past, in consideration of those who stayed throughout the post-accident chaos in Fukushima, or to avoid tensions when they re-enter their local communities. Some of these ‘invisible evacuees’ have even asked their children to tell friends that they left Fukushima “because of Dad’s job.” In Morimatsu’s view, all this does is to negate a formative part of these children's lives. As Morimatsu tells her own children, “There is no need to hide the truth. There is no shame in being an evacuee. The problem is with the society that makes people feel they have to hide their stories.”

“I don’t know what my children think of the work I do, but I like to think that at least they understand my values and know what I think is important. I want everyone to realise that we owe it to the next generation never to let go of the rights we are entitled to.”

- *Following the Fukushima Daiichi accident, the Japanese government set the threshold for evacuation orders to an annual airborne dose of 20 millisieverts. Before this, the annual dose limit in Japan was 1 millisievert. Although the radiation levels in inland Fukushima prefecture did not reach the new threshold, radiation levels were reported as being several hundred times higher than they were prior to the accident.

- **Internally displaced persons, as defined by the Guiding Principles on Internal Displacement, are “persons or groups of persons who have been forced or obliged to flee or to leave their homes or places of habitual residence, in particular as a result of or in order to avoid the effects of armed conflict, situations of generalized violence, violations of human rights or natural or human-made disasters, and who have not crossed an internationally recognized border.”